Teaching people to change the way they articulate sounds is challenging. Over the years, I have realized that instruction guided by principles is more successful and rewarding than instruction guided by, well, by casting about for something, anything, that might work. I came across this quote lately, which got me started in defining my own principles.

Inspired by Mr. Emerson, I have tried to define my own set of guiding principles. Here is #1.

We are designed to perceive, sort, organize and create patterns in our brains, and it is wonderful. We can capitalize on that part of our nature by presenting these amorphous English sounds, these impossible-to-quantify-and-describe momentary sounds, in different sensory systems or patterns, so adults can organize and see the patterns, and understand them. If you are working with an adult intermediate or advanced level ESL or EFL who wants to change their sound, or improve their sound, you are probably speaking to a very smart and educated and ESLed or EFLed person, right? But written English, which most ESL and EFL learners use as their reference framework, and spoken English, which these same folks believe should be representative of the written word, have little in common. When adults see the written word, they cannot help but say the sound they already have come to associate with that visual stimulus. If they have an accent, it means they are saying a sound from their L1, rather than an English sound.

So let’s use a system or pattern or framework that is not associated with spelled English, at least not at the beginning. Let’s start from scratch a build a different system. Let’s build a more logical structure, one that is not associated with spelling, which didn’t really work out so well for some of the people we now work with.

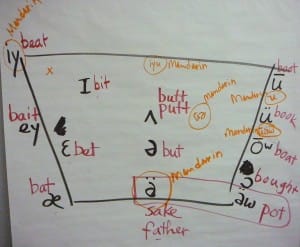

We begin with an intensive review and reconsideration of vowels and consonants. After I discovered the website Phonetics: The Sounds of English I threw out half of the materials that I was lugging around. This website’s illustration and organization of the patterns in English are just what I needed to show adults an entirely new way to think about English sounds—a system of patterns based on sound, not letters. It’s organized in such a brilliant way that once you have worked your way through the sounds with a student, once you’ve discussed how and why sounds are organized in such a way, you won’t need many other resources. If you are working with advanced-level degreed professionals, this will feed their brains; it offers an interesting new way for them to consider English sounds, and provides you with a valuable “third point” for future conversations and reflections.

You may remember that the above principle suggests that pattern making may also HINDER learning. A brief explanation: if we hear about something that we’ve heard before, our brains automatically add it to existing mental frameworks. A phenomenon occurs in the mind–the “oh I already know what this is about” phenomenon, which can cause new features to be overlooked by our brains; we simply and efficiently process it into a pre-existing framework, and whatever doesn’t really fit or match (i.e. new and unique information or skill) just slips away. It doesn’t register. It doesn’t stick. There are no hooks for it to hang on; no home for it to live in. Our brains recognize things that confirm or strengthen existing ideas or patterns, and overlook the new stuff. Watch this YouTube video of that very thing happening: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eVtCO84MDj8

So…how can we master or control what we might not even notice?

Ahh, this question led to Principle #2.

A really great way to make brains “sit and up pay attention” is to surprise them. By creating periods of disequilibrium, we create a period when all a person’s senses are attending, all their mental networks are at-ready to analyze this unexpected strangeness that is happening. When brains don’t know what to do with an experience, they are primed to build a new framework for English sounds. I use every way I can to teach without using traditional terms or methods.

For advanced-level English speakers who have big problems with pronunciation, we start from scratch, relearning vowels and consonants. Here is what I tell them: “The fundamental features of English are different from those of your first language or you wouldn’t be struggling with the sound of it. Starting over, with vowels and consonants, and moving outward in larger and larger speech events, shown below in larger ripples or rings. We adjust the same 5 dynamics to control and adjust our sound in English. Once you understand how these 5 dynamics work, you will be able to control your sound in English better, and you’ll understand native speakers better too!”

The 5 dynamics are duration, voicing, pitch, energy, and clarity, but I don’t introduce them as dynamics, and I don’t introduce them all at once. Instead, as we reconsider each English vowel and consonant using Phonetics: The Study of English, I introduce the dynamic that is important for that discussion.

We always begin with vowels because without the ability to adjust the durations of stressed and unstressed syllables, word comprehensibility won’t improve. It’s the vowel that provides the stretch and lengthening of the stressed syllable. The 2 dynamics that become most important to talk about first are voicing and duration (voicing: all vowels are voiced; vocal chords are important tools)

(duration: stressed vowels are held for longer durations in English).

Because the Uiowa website is heavy with information, perhaps overwhelmingly so, I slow down the conversation and the overwhelming amount of input by creating a “third point” for our work and talk (see example below). This is created as we learn about each sound, so we take a new piece of information about vowels and “transfer” it onto a chart in our room, building the chart as we can. This prevents the extra, new, unique information from sliding away when their brains get “full”. We have anchored it to our chart, and we both know what it means there. We are building a new understanding, a new system together. This is how we try to give form to English sounds, and how I help them begin to realize that things are happening inside their mouths that they weren’t aware of (who goes around thinking about how L1 sounds are made as we talk? only English pronunciation geeks, for sure).

Then we return to the Uiowa website, and continue with consonants, discussing the variable dynamic of clarity (many consonants are voiced, but some are not. they come in +/- pairs). While the student is trying to absorb all this unique information, we are also comparing their pronunciation to the model’s sound and discussing what needs to change inside the mouth. By the end of this vowel/consonant phase, we have discussed which vowels and consonants must be relearned or fine-tuned, and which are just fine. We have also discussed what they must articulate differently, and they know exactly what their home practice should be (practice in hearing and forming targeted problem sounds). In addition, we have laid a groundwork for understanding the importance of adjusting the duration, clarity and voicing of vowels and consonants, why it happens and how it happens, and we’ll use it again when we examine the dynamics of syllables and words.

This brings us to principle #3.

So. Here is the obvious. We are trying to discuss something that happens without our consent really. Do you tell your tongue to go touch the alveolar bumps and stay there for a bit, while you instruct the vocal chords to vibrate just so? Neither do I. Thinking about pronunciation, explaining about pronunciation, describing systems of sounds….all of these is good for the mind but makes no difference to the tongue. Speaking occurs when teams of muscles coordinate and act habitually. Speaking is the result of automatic muscle movements performed without our direct instruction or control. Just thinking about everything that must be happening when we speak makes me a bit dizzy. So teachers and students are faced with a challenging question: how can we change something we don’t actually have control over? It makes changing one’s pronunciation seem hopeless.

It’s not hopeless, but it is physical, and the solution is to create disequilibrium and then implement new physical training. We will communicate to the tongue and jaw in a language they understand–the language of muscles and automaticity. When you go to the gym to work on building bigger biceps, you must do “reps”, repeating the same movement, moving your arm in the same direction so the muscles always follow the same path and always repeat the same action. My point is, you do the same movement over and over. It’s physical. You can’t think your way to bigger biceps. If you injure yourself and receive physical therapy, they don’t just tell you about what you should be doing (although there’s amazing new research that suggests thinking can improve muscle condition), the therapist gives you movements to repeat, each time helping you perform the movement until you can do it on your own. You do ‘reps’. Well, guess what helps improve pronunciation? Reps. Not only are we asking for repetition of physical tongue movements and jaw movements, we are creating repetition of sounds and rhythms, and with repeated tries, sounds become more comfortable and automatic and recognizable.

I have two kinds of workouts, one for sound approximation, using minimal pairs of words in which only one sound is different, and the other quite different, but very physical also, for reinforcement of new muscle learning. Over many many many client experiences, I’ve tested and fine-tuned a set of gestures and christened them The Gesture Approach ©. These movements have wonderful effects: they slow down the speaker as they practice the sounds of English, and they link other muscle movements, larger ones, to what is happening inside the mouth during articulation. They actually perform like “workout buddies” for the tongue and jaw and articulation parts. Tying these together seems to bypass the thinking part of the brain and offers a way to reinforce and strengthen pronunciation of segmentals–like a jogging partner, your actions are reinforced if someone else does it with you. OK, it’s more technical than that, and if you want to know more, contact me about a Masters Class and I’ll explain what I can of the neurolinguistics behind it.

On to principle #4.

So we have given our students a framework for new understanding. We’ve upset the apple cart, so to speak, so they can process the new information into newly created patterns and systems. We have built in physical training to approximate a new physical movement.

Awareness: check!

Consciousness: check!

Permanent Change: hmm. Will students make permanent change or will they lose their new learning and revert to old habits?

Auditory chanting, following various pronunciation models, can strengthen one’s pronunciation. Dr. Olle Kjellin, who holds a medical degree and a Ph.D. in speech, has written a remarkable white paper on the neurophysiological benefits of choral practice. In essence, as a speaker chants or speaks along with a model, their articulation and rhythm gradually begin to match the model’s. This idea brings us to Principle #5.

Of course there is no such thing as perfection, but practice = repetition, and repetitions bring familiarity, and familiarity brings consonance or harmony. What originally felt awkward or sounded strange and disharmonic to students, will eventually sound more natural and harmonic. Our brains are dissonance destroyers by nature—a sound that at first sounds dissonant will eventually seem consonant. We adapt.

The 5 dynamics mentioned earlier are found in all aspects of English sound…and we can teach them in vowels and consonants, then discuss them again when we blend sounds into syllables, and again when syllables are joined into words. They even shape our phrases and sentences, and our public speaking.

I’ll leave you with a summary of the 5 principles that guide my teaching now: 1) we are pattern seekers, which is our strength but also can cloud our vision; 2) disequilibrium or surprise makes us sit up and pay attention; 3) speaking is unconscious and physical so the solutions must address these two ideas; 4) we can’t change something we’re not aware of; 5) practice makes perfect, and repetition makes the disharmonic become harmonic.

Happy teaching!